Practical Chess Analysis by Mark Buckley

[I wrote the following "book report" during the Winter of 2006/2007.]

A former USCF Master at the club loaned me a book-- Practical Chess Analysis by Mark Buckley. He described it as a lightweight version of Kotov's Think Like a Grandmaster. I don't even think like an A-class player, so PCA seemed closer to my level. Accepting a book on loan obligates me to read it; as the book has big typeface and only 186 pages, I decided to follow through. Though I am only 25% through it, I can say that this book is a winner. The first chapter is about visualization. Loosely based on some advice of the blindfold chess legend George Koltanowski, I made visualization flashcards. There is one card for each square. For example, the "e5" card has "e5" on one side and on the other side:

- black

- b8-h2

- a1-h8

White to get out of check

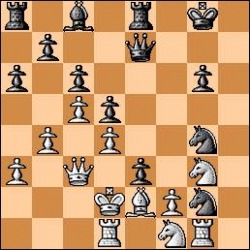

Here is the main line Buckley asks us to follow: 25.fxe3 N2xe3 26.Nxe3 Nxe3 27.Rde1 Qg5. Is the mental picture still sharp? 28.Ne4 Nf1 double ch. If you got lost, do not despair-- I did too on my first reading. I was simply not accustomed to this sort of mental exertion. Buckley gives a few more moves, but the important point is that the long-range pieces have "auras" that shine through other pieces. Eg, the R/g1 has an "aura" that shines all the way down the g-file. Like the CareBear "stare". You know what I'm talking about, Camp Champ. Buckley ups the ante with a Tal example. Buckley's discussion is so easy to follow that he almost convinced me that I could pull off the same sort of shenanigan. (Yeah right.) From Tal - Larsen, 6th match game, 1965:

Here is the main line Buckley asks us to follow: 25.fxe3 N2xe3 26.Nxe3 Nxe3 27.Rde1 Qg5. Is the mental picture still sharp? 28.Ne4 Nf1 double ch. If you got lost, do not despair-- I did too on my first reading. I was simply not accustomed to this sort of mental exertion. Buckley gives a few more moves, but the important point is that the long-range pieces have "auras" that shine through other pieces. Eg, the R/g1 has an "aura" that shines all the way down the g-file. Like the CareBear "stare". You know what I'm talking about, Camp Champ. Buckley ups the ante with a Tal example. Buckley's discussion is so easy to follow that he almost convinced me that I could pull off the same sort of shenanigan. (Yeah right.) From Tal - Larsen, 6th match game, 1965:

White to play a typical Tal move.

Here, Tal played the obvious move, 16.Nb5. Buckley asks us to follow Tal's psychedelic excursion for some 10-12 moves before opining in a grand understatement: "One can marvel at the analytic skill necessary to unearth 25.Be8! [justifying 16.Nb5] ten moves in advance." Indeed. I won't bother with the variations, but suffice it to say that I would feel very proud of finding 25.Be8 on my 25th turn. Tal's calculative powers were legendary; I recall quotes from Botvinnik to the effect that only a fool would challenge Tal in a calculation-heavy melee.

The second chapter covers intuition. With apologies to Mr. Buckley, I will paraphrase and oversimplify: intuition tells you which questions to ask, but hard calculations tell you the answer. Without tactical justification, adherence to general principles can be disastrous due to subtle variance in the position. See also J. Nunn's upbraiding of I. Chernev in the Preface to GCMBM. Buckley gives some examples where a weakness in the enemy camp is exploited. In some instances a direct siege fails, but the defense is demobilized such that the fatal blow occurs elsewhere. Buckley makes the point that knowledge of theoretical endgames can make one's transition thereto purposeful and goal-oriented. Buckley gives moves 52-end of Botvinnik - Fischer, Varna 1962 to show how the wily Soviet champion steered the game into a theoretical draw.

In my opinion, any book that I can actually, realistically read is a good book. This rules out many time-honored "classics" that are either over my head or completely BORING... A good book (like PCA) sharpens the mind, entertains, and doesn't pretend to be a doctoral thesis. I get the impression that a few chess authors forget that they are not saving lives or changing the world. Chess is merely chess, after all-- a somewhat frivolous diversion which for me is a social/intellectual substitute for more passive addictions such as TV, movies, cable and other mass media.

Here, Tal played the obvious move, 16.Nb5. Buckley asks us to follow Tal's psychedelic excursion for some 10-12 moves before opining in a grand understatement: "One can marvel at the analytic skill necessary to unearth 25.Be8! [justifying 16.Nb5] ten moves in advance." Indeed. I won't bother with the variations, but suffice it to say that I would feel very proud of finding 25.Be8 on my 25th turn. Tal's calculative powers were legendary; I recall quotes from Botvinnik to the effect that only a fool would challenge Tal in a calculation-heavy melee.

The second chapter covers intuition. With apologies to Mr. Buckley, I will paraphrase and oversimplify: intuition tells you which questions to ask, but hard calculations tell you the answer. Without tactical justification, adherence to general principles can be disastrous due to subtle variance in the position. See also J. Nunn's upbraiding of I. Chernev in the Preface to GCMBM. Buckley gives some examples where a weakness in the enemy camp is exploited. In some instances a direct siege fails, but the defense is demobilized such that the fatal blow occurs elsewhere. Buckley makes the point that knowledge of theoretical endgames can make one's transition thereto purposeful and goal-oriented. Buckley gives moves 52-end of Botvinnik - Fischer, Varna 1962 to show how the wily Soviet champion steered the game into a theoretical draw.

In my opinion, any book that I can actually, realistically read is a good book. This rules out many time-honored "classics" that are either over my head or completely BORING... A good book (like PCA) sharpens the mind, entertains, and doesn't pretend to be a doctoral thesis. I get the impression that a few chess authors forget that they are not saving lives or changing the world. Chess is merely chess, after all-- a somewhat frivolous diversion which for me is a social/intellectual substitute for more passive addictions such as TV, movies, cable and other mass media.

The lender of this book reminded me to read it, so I’ll be finishing this series based on Practical Chess Analysis by USCF Senior Master Mark Buckley. The lender, who peaked at 2290, rates it as more useful than Kotov for U2000 players. My idea is to solidify the knowledge I've gained by writing it down, and also to give limited benefit to readers of my blog-- while respecting Buckley's copyright of course. (You should track down the book for yourself for the full pedagogic effect.)

Chapter 3: Preparing to Analyze. Buckley is critical of annotators who make unsupported evaluations: “When annotators give general conclusions without accompanying analysis, the reader is often misled: it appears that intuitive judgment alone solved the problem. The truth is that the generalization is probably the result of some tactical analysis.” However, Buckley seems to conclude that the omission is not fatal: “Serious readers then know where to investigate, casual readers know what is happening, and editors save space.” I would add to this list: readers are not reminded of calculus homework, and publishers sell books.

There is no good nor bad but thinking makes it so. -Shakespeare

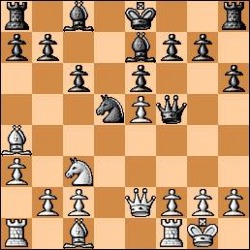

Yet, consider how many sound moves are rejected out of hand because they violate some vague principle. Buckley gives many examples, but I’ll just give one. In Huebner - Korchnoi, Solingen 1973, it was Korchnoi to move after 13 moves:

Chapter 3: Preparing to Analyze. Buckley is critical of annotators who make unsupported evaluations: “When annotators give general conclusions without accompanying analysis, the reader is often misled: it appears that intuitive judgment alone solved the problem. The truth is that the generalization is probably the result of some tactical analysis.” However, Buckley seems to conclude that the omission is not fatal: “Serious readers then know where to investigate, casual readers know what is happening, and editors save space.” I would add to this list: readers are not reminded of calculus homework, and publishers sell books.

There is no good nor bad but thinking makes it so. -Shakespeare

Yet, consider how many sound moves are rejected out of hand because they violate some vague principle. Buckley gives many examples, but I’ll just give one. In Huebner - Korchnoi, Solingen 1973, it was Korchnoi to move after 13 moves:

Korchnoi played the provocative 13...b6 and unleashed a characteristic counterattack on the queenside. Most players would reject this move on principle for fear of the g2-a8 diagonal. Yet Korchnoi saw that the e4-knight has no SAFE discovery square-- after the knight’s harikari and Bxa8, then Black will get 2 pieces for his rook after Bc8-e6 and Qxa8, with material and positional advantage. 13...b6 is an attractive move, instantly solving the problem of developing the c8-bishop and preparing to grab space with c7-c5. To paraphrase Buckley, general principles tell you what questions to ask; specific variations give you the answer. A player who relies on general principles for the answers will play vague, superficial chess. This is the crux of the whole Maza revolution. The last bit of the chapter covers The Threat Hierarchy. Strong players rank threats from strongest (eg, mate) to weakest (eg, doubled pawns) and naturally analyze the strongest threats first. That’s intuitive enough. Buckley suggests assuming it is your opponent’s move (when it is actually your move) at the start of your analysis. With an idea of the opponent’s (biggest, baddest) threat, a counterplan may be devised.

Chapter 4 covers pawn structures. Buckley gives examples of identifying and exploiting weak squares, such as Donner - Fischer, Santa Monica 1966 (Fischer’s target is c4), and Lasker - Steinitz, 9th Match game 1894 (Lasker wants d6). The best part of this chapter was the section on pawn breaks. Consider Nimzowitsch - Rosselli, Baden Baden 1925. Click on the game link for a PGN with Nimzo's annotations.

Chapter 4 covers pawn structures. Buckley gives examples of identifying and exploiting weak squares, such as Donner - Fischer, Santa Monica 1966 (Fischer’s target is c4), and Lasker - Steinitz, 9th Match game 1894 (Lasker wants d6). The best part of this chapter was the section on pawn breaks. Consider Nimzowitsch - Rosselli, Baden Baden 1925. Click on the game link for a PGN with Nimzo's annotations.

The side with tactical opportunities is the side with the pawn breaks. White has five pawn levers: b3-b4, c2-c3, e4-e5, g2-g3, h3-h4. Black has to calculate the tactical implications of each of these (and all permutations) at every turn! This little section was the most educational for me-- I usually employ the cavalry/clergy, not infantry. Stay tuned for later chapters.

Chapter 5 covers piece placement. I would draw an analogy to hockey’s penalty box to describe the idea of the misplaced piece. When a piece is in the penalty box (ie, out of play), the opposing side can achieve a “power play” with numerical superiority on the other side of the board. For example, in Portisch - Petrosian, Santa Monica 1966, Petrosian queen’s knight was stranded on the queenside while the castles burned on the kingside. The less intuitive version of the misplaced piece involves duplicity of function. When pieces guard the same squares, they trip over each other and accomplish less. Note that this is why the bishop pair is so efficient: it is impossible for them to duplicate functions. In the following position from Karpov - Parma, Caracas 1970, Black has just made what Karpov dubbed the losing move. (!!)

18...Nc5-e6 looks innocent enough, but the knight here merely duplicates the work of the pawns, who work for cheaper wages. Black realized this soon enough, and re-routed the knight via e6-c7-e8-f6, bringing the knight to f6 in four tempi instead of e4-f6 which expends only two. Against Karpov’s technique, those two misspent tempi were the difference between a draw and a loss. Buckley concludes this section by reiterating the theme that underlies every chapter-- image is nothing, tactical calculation is everything. Before punishing a “misplaced piece”, one needs to calculate to ensure that the punishment is actually enforceable. In Tolush - Keres, Leningrad 1939, Keres saved his wayward knight (on h4) via tactical means. The latter half of the chapter covers hypothetical exchanges. The crux is that abstractly deciding which pieces you’d like to trade off can sometimes inspire a plan of piece placement. To take just one example, in Alekhine - Eliskases, Podebrad 1936, 19.Bg5 could be (1) conceived via the abstract judgment that the absence of dark-square bishops is preferable for White and then (2) justified via calculation. Additionally, pawn structure often dictates piece placement. In Portisch - Fischer, Interzonal 1967, after 15 moves, each side had accomplished its strategic objective. Drawing on Buckley and my own ideas, I’ll consider the respective plans for both sides. Portisch (White) is to move after 15...b7xc6.

For White: The d-file is open, true, but all the entry points are guarded so this is not much use for now. C5 is very weak; black’s pieces can be tied down defending this point. An endgame would be winning for white due to black’s structural defects and “bad bishop” on g7. Therefore, White would like to trade off everything else-- ie, queens, rooks, and light-square bishops (h3-h4, Kh2, Bh3). White could continue with h4-h5 to trade rooks on the open h-file.

For Black: The d-file is open, but Black should try to avoid rook exchanges (due to Black’s poor endgame prospects). Black’s knight belongs on d4. There it will be a powerhouse, and white will be powerless to exchange it lest a protected passed pawn take its place on d4. The knight can travel to d4 via f6-h5-g7-e6. It may need to hang out at e6, from where it lends support to the weak square c5. That entire game revolved around Fischer’s “threat” to post a knight on d4, though it was never accomplished. Of course, iridescent arrows and vague plans are pretty to look at and simple to comprehend, but don’t forget that cold calculation must justify them in the final analysis. So, I’m halfway done with the book! I’m tempted to buy it from the lender; he quoted me $10.

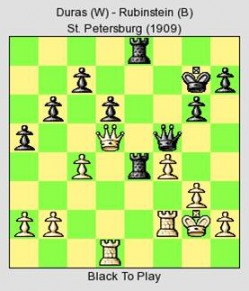

Chapter 6 is titled Open Lines. Pawn structure dictates open lines, and open lines dictate planning. In war, both armies attempt to control ports, roadways, and other avenues of transport. Open lines are the chessic analogue—with the center being the most-traveled intersection. Buckley notes that an open line (or “positional artery”) has only potential value. Open lines must be valued in connection with the plans and schemes they facilitate. Buckley gives Duras - Rubinstein, St Petersburg 1909 to show how Rubinstein cashed in on his control of the e-file highway.

There is not a crash-through tactic here! The point is more akin to a siege. Black has a deadlock on the only open line; White can hardly do anything constructive at all. So how can Black exploit this fact to create a weakness? Black is not in a hurry.

[ h7-h5-h4xg3 to weaken g3 and open the h-file. Subtract points if you said Re2 or Re1-- these only encourage exchanges and ease pressure on White. ]

The next section is a terrific primer on how to handle IQP positions. Buckley basically refutes the suggestions of Nimzowitsch's My System in this regard, opining that "Against proper defense, [Nimzo's] method gives few chances for the initiative." Nimzo's method is too slow! Buckley gives a couple illustrative games:

Chapter 7 covers two perspectives of the same sort of position: Attack and Defense. Buckley notes one aspect that favors the defender: "One trump of the defender is his limited goal: he need only find a single line that successfully holds. In contrast, the attacker must analyze and refute every reasonable defense-- unless he speculates. Learn how to punish such gamblers with precise tactics." Once again, the emphasis here is on (surprise) precise calculation. Buckley gives a defensive effort from one of the major contributors to the book's games, Lajos Portisch. (Portisch - Tal, Niksic 1983) Buckley gives a 7-step method for prosecuting the attack. Much of this is very intuitive to a student of Vukovic, though it is a helpful outline nonetheless. One of the cooler ideas is to map out pathways for all your pieces to reach the enemy king. Impractical pathways suggest disposable pieces that can be sacrificed for more immediate ends. (Or maybe an ill-advised attack in the first place!) Buckley emphasizes the importance of flexibility; Vukovic iterates the same concept in his discussion of changing "focal points" mid-attack. It may even be advantageous to abandon the attack altogether for an advantageous endgame. Buckley says that "you must be ready to abandon a scheme the moment it achieves maximum concessions" from the opponent-- a useful lesson. Buckley cites the games of Fischer as models in the art of "exchanging advantages". E.g., an opening space advantage ==> a kingside attack ==> superior minor pieces ==> opponent's pawn weakness ==> winning endgame.

[ h7-h5-h4xg3 to weaken g3 and open the h-file. Subtract points if you said Re2 or Re1-- these only encourage exchanges and ease pressure on White. ]

The next section is a terrific primer on how to handle IQP positions. Buckley basically refutes the suggestions of Nimzowitsch's My System in this regard, opining that "Against proper defense, [Nimzo's] method gives few chances for the initiative." Nimzo's method is too slow! Buckley gives a couple illustrative games:

- Uhlmann - Karpov, Leningrad 1973. Uhlmann played according to Nimzo's method and never had a chance.

- Browne - Zuckermann, Atlantic Open 1973. Browne provides a model attacking game.

Chapter 7 covers two perspectives of the same sort of position: Attack and Defense. Buckley notes one aspect that favors the defender: "One trump of the defender is his limited goal: he need only find a single line that successfully holds. In contrast, the attacker must analyze and refute every reasonable defense-- unless he speculates. Learn how to punish such gamblers with precise tactics." Once again, the emphasis here is on (surprise) precise calculation. Buckley gives a defensive effort from one of the major contributors to the book's games, Lajos Portisch. (Portisch - Tal, Niksic 1983) Buckley gives a 7-step method for prosecuting the attack. Much of this is very intuitive to a student of Vukovic, though it is a helpful outline nonetheless. One of the cooler ideas is to map out pathways for all your pieces to reach the enemy king. Impractical pathways suggest disposable pieces that can be sacrificed for more immediate ends. (Or maybe an ill-advised attack in the first place!) Buckley emphasizes the importance of flexibility; Vukovic iterates the same concept in his discussion of changing "focal points" mid-attack. It may even be advantageous to abandon the attack altogether for an advantageous endgame. Buckley says that "you must be ready to abandon a scheme the moment it achieves maximum concessions" from the opponent-- a useful lesson. Buckley cites the games of Fischer as models in the art of "exchanging advantages". E.g., an opening space advantage ==> a kingside attack ==> superior minor pieces ==> opponent's pawn weakness ==> winning endgame.